The COVID-19 pandemic presented unprecedented challenges to education in African countries. In response, researchers have mobilized to produce actionable evidence that supports system recovery and resilience. What can this experience teach us about the ability of education systems to absorb the shock of a crisis? How can research help assess—in real time—government efforts to change policy and practice to sustain learning? And how can we turn the learning losses suffered by students into valuable lessons for the future?

This is how the KIX Observatory project came to be. Starting in 2021, researchers worked to collect and synthesize policy and practice responses of 40 partner countries of the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) in Africa. Focusing on two main areas—the operation of education systems and the wellbeing of learners—researchers examined the following topics: education financing, the psycho-social wellbeing of school children, school reopenings, teacher training and support, and learning assessment.

Findings from the research on COVID-19 impact on school systems

Financing education responses to COVID-19. All GPE partner countries in Africa made contingency plans to fund responses related to education disruptions caused by the pandemic. More than half of the contingency funds supported preparations for school reopening and the use of distance learning solutions, while about 6% targeted learning support to vulnerable children, including those with special needs and displaced populations. Although governments drew on existing education, supplementary and special program budgets to provide domestic resources, the funding heavily relied on external sources, such as GPE, the World Bank, UNICEF, and Education Cannot Wait. When available, domestic emergency funding enhanced the ability of education systems to adapt to COVID-19 disruptions. For example, in Ghana, the government and its partners financed content development, curation and delivery of distance learning, and an enhanced digital library. In Cabo Verde, the government supported lesson delivery through radio, television and the use of tablets.

Overall wellbeing of school children. The impact of the pandemic on the psychosocial wellbeing of school children may be one of the longest lasting effects of COVID-19 disruptions to educational systems. Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) increased by almost half in partner countries in Africa during the crisis. Child helplines and violence prevention services were disrupted, with 57% and 71% of countries in Eastern and Southern Africa, respectively, reporting at least one form of disruption.

On a positive note, countries in the Sahel region—one of the areas most affected by SGBV—instituted child helplines to reach more children. They also made positive parenting resources available, and enhanced training on child-friendly counselling. Countries within the Lake Chad Basin, and Kenya and Sierra Leone used community-based resources and media campaigns to stop violence against women and girls and limit teen pregnancy.

Another significant impact: school closures and country lockdowns meant some 350 million children no longer had access to school meals. Countries like Liberia and the Republic of Congo addressed nutritional gaps for about 100,000 and 61,000 children, respectively, through the delivery of school meals to student homes. Other strategies used to promote children’s wellbeing included supplying menstrual health management information to girls using targeted platforms such as YouTube and Oky.

School reopenings. More than 60% of GPE partner countries closed schools for over 200 days. Successive waves of the pandemic forced several countries to reclose schools after full or partial reopenings. Except Uganda, all countries in Africa had reopened their schools by the fourth quarter of 2021, driven by the need for learning continuity and limited access to distance learning. Government responses focused on developing decision-making frameworks and health guidelines for reopenings, back-to-school campaigns to encourage all learners to return, and adaptations to learning after school reopenings.

At least two of these responses were witnessed in each partner country. Education systems promoted adherence to health guidelines for mitigating COVID-19 infections through maintaining physical distancing despite large school and class sizes, frequent hand washing, temperature checks and isolating staff and children infected or exposed to the virus.

Learning adaptations after reopening were critical in many countries due to learning loss, which has yet to be fully measured. Countries adjusted physical arrangements to accommodate social distancing; modified class schedules and the school calendar to recover lost learning time; introduced remedial programs and accelerated learning for students to catch up; and instituted partial reopenings that allowed students to take important examinations and helped them gain experience that could be adapted during full reopenings.

Teacher training and support. The role of teachers in building back better education systems is undisputable. All countries in Africa implemented at least one teacher training activity during the pandemic. For instance, 21 countries provided training on the development of lesson plans, teaching plans and guides and instructional models through distance learning solutions. During and after school closures, teacher training and teacher support focused on six areas: development and use of distance learning solutions; support to school children affected by gender-based violence and struggling with mental health; support for vulnerable children; school reopening preparations; teachers’ overall wellbeing; and teachers’ motivation and incentives.

However, even in countries that implemented training, not all teachers were trained—more than half of all teachers were trained in Lesotho, Rwanda and Malawi, while less than 2% were trained in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The limited training of teachers implies an inadequate response to learning needs from students during school closures.

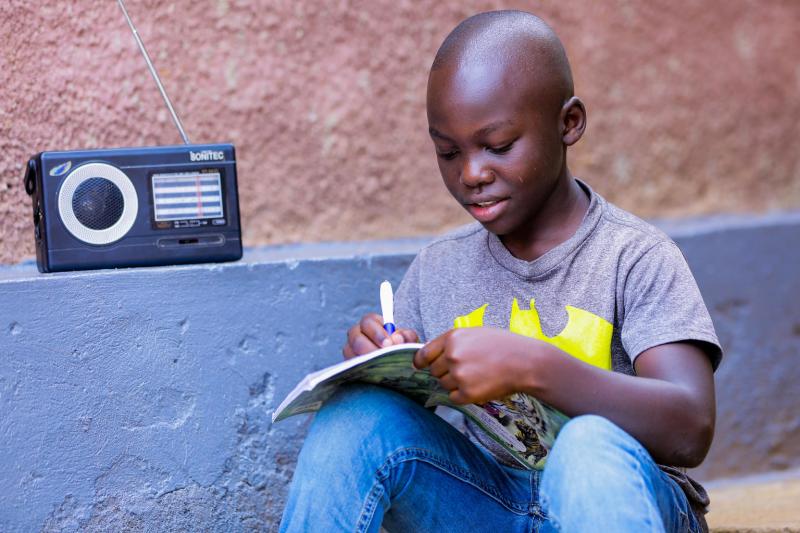

Learning assessment. During school closures, learning assessment hardly took place, even after distance learning solutions were scaled up. This is perhaps due to the inadequacy of distance learning to adapt to the stringent measures required for credible assessments. Nearly all partner countries postponed their high-stakes examinations. Despite their challenges during the pandemic, commonly used assessment practices included homework and assignments that were delivered through live or pre-recorded lessons (e.g., radio and TV), social media (e.g., WhatsApp), specialized academic platforms (e.g., Khan Academy, Seesaw and EdoBEST), mobile phone short messaging services, and web-based platforms (e.g., Zoom and Google Meet). Burundi, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Senegal and Zambia are among the countries that have planned to assess learning loss after schools reopened.

How do we use these findings?

The COVID pandemic showed us that education systems simply were not ready for such a crisis. This one may be slowly abating, but more are sure to come. So, what do education systems in Africa need to do to be more resilient next time?

The KIX Covid-19 Observatory’s syntheses highlighted key lessons for decision makers in the education sector in Africa:

(1) They must generate domestic resources for emergency responses in education to create sustainability. A portion of such resources should be allocated to promoting equity and inclusion to help ensure vulnerable children, including girls and children with special needs, can access education services.

(2) Education systems should reinvigorate monitoring systems for sexual and gender-based violence, mental health and food security among vulnerable children. This is best done at the community level.

(3) They must strengthen contingency planning to better respond to future education disruptions. Such plans should reflect the most current research evidence and best practices.

(4) There should be more resources invested in training teachers, as frontline workers, to enhance pandemic coping mechanisms and reverse learning losses.

(5) Countries should improve the effectiveness of assessments during crises. Some ways of doing this include mainstreaming digital technology in assessment systems and enhancing the resilience of education systems to adequately respond to assessment needs. At minimum, learning assessment should be part of ongoing conversations around education technology (EdTech), which is likely to occupy education systems in unprecedented ways.

The COVID-19 pandemic was devastating in many ways, including its impact on education systems. But it has also offered many valuable lessons that countries can draw on to better prepare for other crises, in hopes that learning will continue during future disruptions.