“What have you done to my child?” These were the exact words expressed by a Kenyan parent during a graduation ceremony for teachers who had participated in a teacher professional development (TPD) program on early literacy instruction and the use of ABRACADABRA (ABRA), an early literacy tool offered with the Learning Toolkit (LTK)[1]. Initially stunned by this question, we were quickly relieved to learn why she posed it. Her son had been disenfranchised with school following the death of his father and was at risk of dropping out. Yet after the integration of ABRA into her son’s English lessons, she had seen a transformation in her child. He was motivated to attend school, was teaching her English literacy at home and was one of the top students amongst his peers. Wonderful news!

What would have become of this young child had he not been introduced to this software? The statistics on illiteracy and dropout rates in the Global South are staggering and crushingly negative. The World Bank and others (2022) spoke to the grave risk to hundreds of millions of children around the world, and their societies, if children do not acquire the basics of literacy and other foundational skills.

More than ever, teacher professional development (TPD) programs on early literacy instruction and the use of ABRACADABRA (ABRA), an early literacy tool offered with the Learning Toolkit (LTK) are essential if we are to reverse this troubling trend. In our approach to TPD, now using a blended approach[2], we have focused on both the skill and will components of technology integration into everyday classroom routines. We not only focus on what to do, but why and how, using a process of initial TPD guided by the evidence, followed by ongoing support. And especially for teacher motivation (the “will” component), we’ve adopted an important theory well suited to the challenges of educational innovation known as Expectancy-Value. This model posits that innovative practices are related to positive expectations of success, valuing of transformative experiences and minimization of perceived costs.

Expectancy relates to teachers’ perceptions of the contingency between their use of the strategy and the desired outcomes, and factors affecting these perceptions including internal attributions (such as teacher self-efficacy and skill), and external attributions (such as student characteristics, classroom environment and collegial support).

Value assesses the degree to which teachers perceive the innovation or its associated outcomes as worthwhile including benefits to the teacher (such as congruence with teaching philosophy, career advancement), and to the student (such as increased achievement, improved attitudes).

Cost, related to the perceived physical and psychological demands of implementation, operates as a disincentive to innovating and may include class preparation time, effort, and specialized materials. In short, for any new educational innovation, a teacher must believe she can implement it successfully, that the efforts at change are worth it, and that the benefits outweigh the costs.

An expectancy-value success story

One teacher’s take up of ABRA can help to illustrate this model at play.

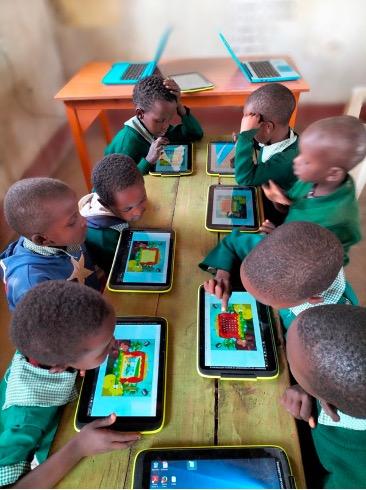

We first met Chepngetich Naomi in 2016 during an ABRA TPD session in Kirindon, an isolated and often neglected region of Western Kenya. Naomi was an early primary teacher at Kimintet Primary School, that had a mixture of 43 laptops and tablets powered by solar panels. As a result of this session, Naomi expected she could use this interactive software with her young students, saw its value and readily started to integrate it into her grade 2 English class with a ratio of 4:1 computers per child.

Within a short period of time, her colleagues sought out her support and she became an ABRA Ambassador, a designation applied to teachers who served as coaches to their peers.

She describes her initial journey:

“I attended the first ambassadors’ training in KIRINDON ADP in 2016 and I was awarded a certificate of participation. I was so grateful. I then attended the second and third training too as a resource person/facilitator. Follow up support from World Vision has been of high value as far as LTK implementation is concern. Provision of accessories to name a few, has made my teaching easy and learner centered.”

Over the years various national programs were implemented in Kenya, such as the Tusome literacy program and the Digital Literacy Program (DLP), yet Naomi continued to discover ways of optimizing use of the tool within this dynamic pedagogical environment.

As well, she co-facilitated TPD sessions, coached her peers through online platforms and spoke at conferences. In an end of year report on her use of the software, Naomi speaks to the value of using ABRA:

“[The] LTK has improved performance in my class in that absenteeism, which was rampant, decreased since the introduction of LTK LESSONS - nobody wants to miss it. Together with TUSOME, LTK has enhanced increase in enrolment. Students from schools not using LTK shifted to our school, Kimintet Primary, especially the lower grades. There have been noticeable reading skills acquired, activeness and ability to solve problems. There has been an improvement in literacy and numeracy in lower grades.”

Following the pandemic in 2021 Naomi was transferred to Nkuseron Primary School in Kajiado, another remote region but this time outside of Nairobi. While this school had been outfitted with the DLP devices, given their longstanding lack of use, technical issues ensued with the server. Not to be deterred, Naomi used her personal phone to tether the tablets such that her students were able to access the software. While Naomi was out of pocket given the data costs associated with using her phone, these were insignificant costs, given the expected success and value of using the tools.

Another school transfer in 2023 brought Naomi back to Kirindon to Esoit Naibor Primary School, a neighbouring school to Kimintet Primary, and along with it her continued use of ABRA. She writes:

“Looks like I am now an LTK addict. Can't do without it in classroom. By the way, I was assigned without objections to grade one!! Including the parents, they were so excited that I was back from Kajiado and that the school will now rise!! Especially in literacy (English Language)... There's no magic here! It's the LTK I am using!”

In the last several years, and throughout the pandemic, funding from the Global Partnership for Education Knowledge and Innovation Exchange (KIX), a joint endeavour with Canada’s International Development Research Centre, has allowed us to continue and expand our work focusing on barriers and facilitators to scalability and sustainability. Working with the Aga Khan Academies, World Vision and Wilfrid Laurier University, we have adapted our face-to-face TPD to a blended approach—online with some face-to-face support—with an eye to proven effectiveness and increased efficiency. Parents, NGOs, government organizations are noticing and asking “What have you done to our teachers?”

[1] The interactive tools within the Learning Toolkit have been developed at Concordia University (Montreal, Quebec) and are available without charge. ABRACADABRA and its accompanying online TPD material) are accessible from literacy.concordia.ca/en

[2] This work was supported by the Global Partnership for Education Knowledge and Innovation Exchange, a joint endeavour with the International Development Research Centre, Canada